Origami and the associated maths

Published November 09, 2015

'ey.

.

So this is going to be another one of those write-it-out-so-that-I-can-better-understand-it sort of things. Just a heads up. This IS a journal, after all, and functions as advertisement second.

.

So. Origami and mathematics. We know that the two are related because, if you fold a piece of paper the same way twice, you'll get two of the same shape, so there's rules governing it. And some smart people have tried figuring out those rules. There's a bunch of them, but they all fall short for what I'm wanting to do. So here it goes:

.

Together with research in 1992, and again in 2002,

a total of 7 axioms for flat folding paper were created, detailing exactly which basic operations could be performed with paper. These were laid out in much the same way that Euclid's axioms of geometry were laid out. This is basically the way that most research that I've been able to turn up on the internet is: interesting constructions that, using the axioms, prove something about something else.

.

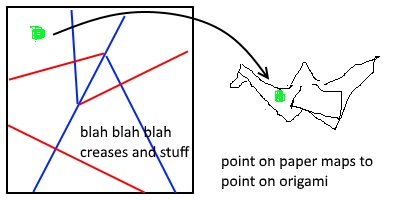

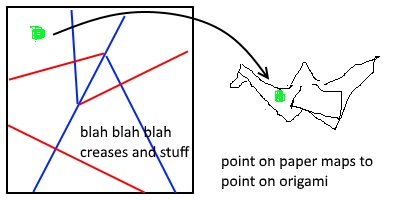

What I'm wanting to do, however, is a lot different. I'm wanting to be able to take a collection of creases and their associated information, and turn it into a model of the finished product. A kind of crease instruction to finished origami model converter if you will. To do this I've tried a couple methods, like physics based, relaxation and constraint based, and they've failed for one reason or another. I've settled on doing something sort of finite-element based: given a point on the original piece of paper and all the folds, where will that point be located in 3D space?

.

(turn up for trackpad art)

.

Unfortunately, there doesn't seem to be any information on the topic, so I guess I'll have to do it. Which is good, because I really wanted an interesting problem to work on. The rest of the entry will be about the stuff I've concluded so far, and the questions I have.

.

Types of folds

.

Folds are what what happen when you crease the paper in a straight line, and either fold the other side down or turn it some arbitrary angle around the fold. I'll be using the term "fold" and "crease" interchangeably.

.

Folds can created that do one of two things:

- start at one edge of a piece of paper and end at another

- loop back in on itself

(a fold can also start and stop on the same point on the edge of a piece of paper, but I'll ignore that case and say it's case #1)

.

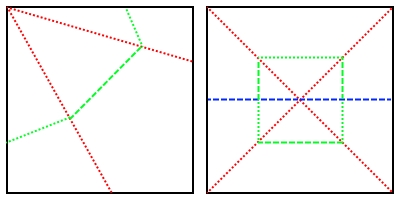

.

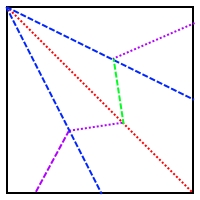

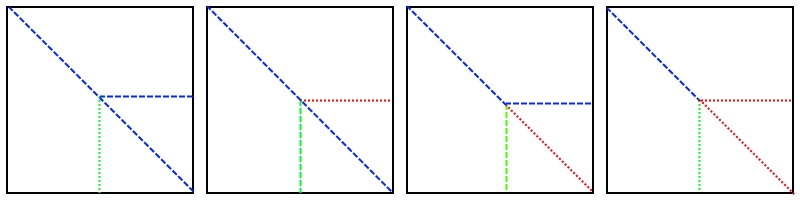

As you can see in the above examples, folds can be segmented into multiple parts going different directions, but are still connected end to end. I'll call these fold segments. They come in 2 flavors:

- mountain

- valley

These types mean essentially nothing by themselves. They represent a direction to fold relative to your viewing angle. What's important is that they are opposites, and reversing every single fold segment will result in the exact same origami (this is equivalent to turning the piece of paper over). In this journal, all mountain folds are shown as dotted lines in red, and all valley folds are shown as dashed lines in blue, unless i'm trying to point something out.

.

Things you can do with folds

.

Origami is all about layering paper folds, one after another, in order, to create something. The "in order" part is important. You can't create the head and tail of a paper crane (the last steps) before you make all the other folds. However, folds are not always dependent on all of the previous ones. Sometimes folds are made purely to get a reference point for some other fold later on down the line. Some folds cancel out the symmetry of previous folds (more on that later). Further, some steps can be done in parallel, like the 2 wings of a paper plane, because they are independent of each other.

.

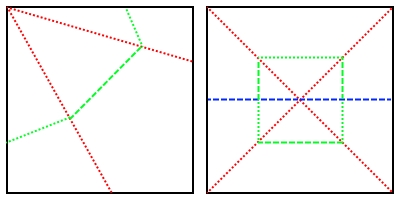

When you make a fold, sometimes the mountain fold that you thought you made is actually a bunch of mountain-valley segments. To clear this up, I'll call the starting fold segment the fold seed.

.

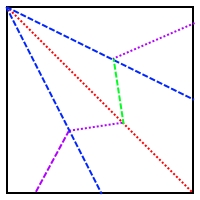

(the green fold segment is the fold seed. The purple fold segments were calculated from other information about symmetry and dependency)

.

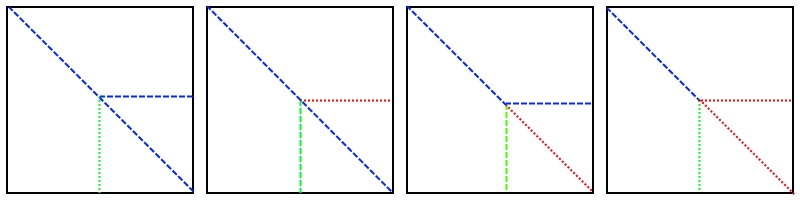

There are 4 types of fold seeds that I'll support for right now. They are:

- mountain

- valley

- inside-reverse (more on this one later)

- outside-reverse (the opposite of inside-reverse)

(from left to right: mountain, valley, inside-reverse, outside-reverse. The green is the seed, and this shows what happens when each fold interacts with a single dependent)

.

I chose these specifically because these are the types of fold seeds that are needed (with the exception to #4) to create a paper crane. I figured if I can't create a origami interpreter that can't interpret the quintessential piece of origami, I've failed. The first 2 are really obvious and the latter two I'm saving for a later time. There are certain issues about them that make them more complicated.

.

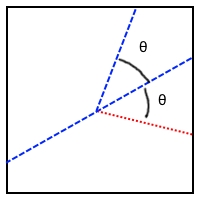

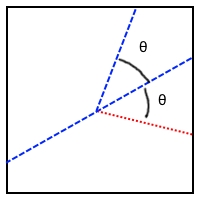

You've likely noticed in all of the pictures you've seen so far there's a lot of reflection about lines going on. I'll call this reflecting about lines "dependency," because of the its ordering properties. When a fold segment is dependent on another fold segment, it will reflect about the other line and change from mountain to valley or vice versa. Here's a pic:

.

.

An important thing to note about this dependency is that the line that is being reflected about *has* to be done first. The only exception to the rule is fold segments at 90 degree angles on the paper, which can be done interchangeably (which I think says something very interesting about these types of folds).

.

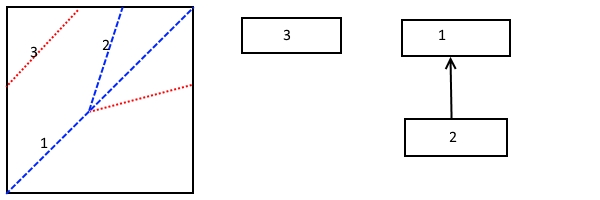

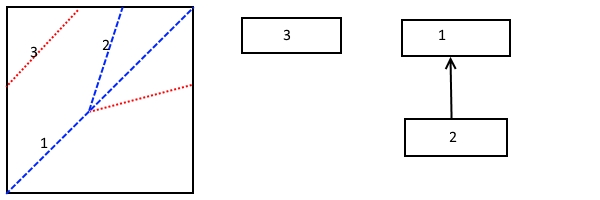

All of the above info has led me to use a tree to talk about origami folds. the parents of the tree represent dependency, while the nodes represent fold seeds.

.

.

For mountain and valley fold seeds, this representation encompasses everything that needs to be said about an origami: from parallelism to dependency to ordering to direction.

.

Other fun facts

.

Here are just some neat things that happen to be true, that are essential to have a complete implementation of a origami interpreter, but aren't essential to have a complete understanding of what's happening. In no particular order:

- Everything talked about above has to do with planar folds, folds that create something that ends up laying down flat (180 degree folds). Non-planar folds act the exact same way but have an additional constraint: they can have no children in the dependency tree.

- For planar folds, every vertex where fold segments intersect, there are always the number of valley folds segments and mountain ones always differ by 2. For vertexes where fold segments and paper edges intersect, all bets are off. For non-planar fold segments, you can treat them like paper edges for the purpose of counting mountain-valley folds. This is an easy way to tell if a fold is valid or not.

- For mountain and valley fold seeds only, if a fold seed is dependent on a parent, which is dependent on a grandparent, then the fold seed is also dependent on the grandparent. This is not true for inside-reverse or outside-reverse folds.

- Folds that do not touch their parent fold in the dependency tree can be turned into 2 separate folds without any issues. For non-planar folds, it get's a bit more complicated. This is the only time self-intersection of paper is a problem, and I think I can safely ignore this case as it's fairly easy to work around. I think

- Nodes on the same layer of the dependency tree that are not dependent on each other can be done in parallel, or in any order.

- Each node on the dependency tree must be unique, otherwise it'd be kind of hard to do anything with it or conclude anything from it.

Yup.

.

Well that's about it. That's all I'm really semi-confident about at the moment. There are a bunch of things I still have to look into and figure out before all is said and done though.

.

Tune in next time to find out what any of this has to do with finite element transformations, what the deal is with inside- and outside-reverse fold seeds and why they throw a kink in everything, and how any of this will help creating a fold to origami interpreter.

.

See yah!

That's pretty cool. I remember thinking years ago that I would love to see a game or animated movie where there was a character who could shapeshift, not like a werewolf, but like folding himself into different origami shapes. Maybe one day it will be easy for 3D engines to animate origami folding. :)